In research, we think we will find answers, and we end up finding questions. This blog is no exception. Originally, we had simple questions. Passionate about the tattoos worn by women in the Berber regions of North Africa, we spent a lot of time, our noses in books by anthropologists, trying to find the meaning of a tattoo seen in a family photo, or even a guessed pattern on a piece of jewelery or clothing. And one thing led to another, without warning, these questions became more complex and took us to broader horizons… Why did this woman tattoo this motif on her forehead? Who gave him the meaning of this tattoo? How is it that these motifs have traveled through so much time, from Antiquity to the present day, and so many geographical regions? And then one day, there was this question… what is the role of women in cultural transmission?

We had the impression of being faced with an astonishing paradox: in the collective imagination, artistic education and cultural transmission are often associated with women; however, when we think of the great artists of history, we often think of great men.

Women artists, women educators, women guardians of knowledge… What role for women in cultural transmission? We wanted to share with you our thoughts and our readings on this vast subject…

Women and transmission of material culture

One of the ways of transmitting a culture is material. The production of art or crafts allows posterity to leave a mark of its culture: the choice of material, shapes, designs tells a story, the story of a people, of its legends. , of his beliefs…

Women have always played a big role in craftsmanship in many parts of the world. In the Amazigh (or “Berber”) regions, women imagined and created pottery and carpets, an ancestral craftsmanship known throughout the world today. In these pottery and carpets, of which they were the author-artists, they incorporated motifs to tell stories and represent life events: the harvest, a birth, traditional festivals... True creative artists, they passed on their know-how to subsequent generations of women, as well as the symbolism behind the patterns. More than an anecdotal tradition, this act has a strong cultural significance: families decorated their homes with these cultural objects, which were also sold, which ensured cultural transmission to subsequent generations and in other geographical regions ( today, Berber carpets are known all over the world, even if the meaning of their patterns is lost). Embroidery is also a vector of cultural transmission by women in Viet Nam, or by Amerindian embroiderers, in addition to being a means of financial emancipation.

While the role of women in craftsmanship is established in the collective imagination, their place in the art world – for cultures that distinguish art from craftsmanship – has not always been recognized. We know that there have always been women artists, but they were long excluded from art training, then later from museums. Berthe Morisot at the time of the impressionists, or even Kay Sage and Leonor Fini during the surrealist movement contributed to artistic revolutions without their work being really recognized. Françoise Collins writes: “'Represented', women are everywhere in art, but not present. Say but not say. Seen but not showy.” in her article “Between poiêsis and praxis: Women and art”. The website of the Ministry of Culture details here the key dates from which women have had rights of access to the art world (in France, women have been authorized to take the Beaux-Arts competitions since 1897), even if female artists are still in the minority in the biggest museums - and in the world of culture in general (reports by the gender equality observatory here for detailed statistics) -, as a result of centuries of “oversight” of recognition and absence of women's rights. Despite these inequalities of recognition, many women artists have participated and still participate in cultural transmission through art: Edmonia Lewis, Marta Pan, Hend Al-Mansour, Irene Chou, Lorna Simpson, or Hale Asaf are not among them. just a few examples.

Women and transmission of intangible culture

But very often, the culture is not palpable. It is neither material nor written… It is lived through words, gestures, songs, language, gastronomy. All this part of culture, the one that is immaterial, subtle, sometimes even unconscious, women are very often its guardians and vectors.

In her book “The Valor of Women”, Camille Lacoste-Dujardin describes and analyzes the tales that Amazigh women invented and told to children in Kabylie: “tales constitute the essential vector for the transmission of Kabyle representations and cultural values, in the form teaching from one generation to the next.” In particular, she describes the character of the ogress Teryel, and how women used it to convey their messages to subsequent generations.

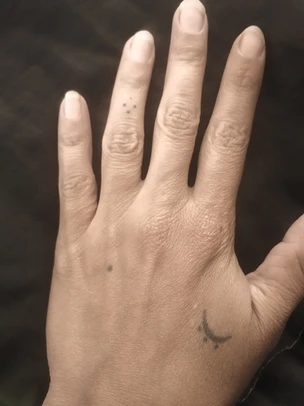

Another form of intangible cultural transmission among Amazigh women is through tattooing. Women tattooed their faces and bodies with patterns with strong symbolism. They told their story and their values. These symbols, they transmitted the meaning to the women of the following generations; thus, the tradition of tattooing and their meaning has been transmitted for centuries in all the Amazigh regions of North Africa, and it still exists today. This transmission is oral and the written traces on the subject are difficult to access, so that this part of the culture risks disappearing with the disappearance of this tradition. These patterns, which represent the different aspects of the Amazigh culture, are also found on pottery, carpets and architecture; their meaning, on the other hand, without the oral transmission of women, is less and less known.

Women and cultural transmission: an invisible role?

Women participate in cultural transmission in all its forms: material or immaterial, art and crafts, song, dance, language, tattoos, storytelling...

Let's go back to our paradox for a moment. How can women be so much at the heart of cultural transmission when art and culture are so often associated with men?

One possible answer comes from the distinction education versus creation. Where men are considered creators, artists, authors, women are expected to educate children, transmit and support culture. In “Women, the arts, and culture”, Marlaine Cacouault-Bitaud and Hyacinthe Ravet write: “The access of women to the professional exercise of an artistic activity, which will then be considered in certain cases as a 'trade ', was realized with difficulty. Sometimes these women, their works and their practices have been made invisible even though their presence is attested. Even today, the place they occupy within the artistic professions remains ambiguous, they are confined to certain fields (for example, to singing rather than to instruments) and to certain functions (teaching and accompaniment versus creation). (...) This research calls into question – at least in part – the boundaries drawn between the sexes and the attribution of the gender of creation, the obvious being often thought of on the side of the masculine creator. They show its historical roots and underline the weight of the representations.” (file to read here).

The representation. An essential means of giving back to women their merit, of recognizing their role in art, in culture and in cultural transmission. Representation is the motivation for writing our book “Women go, and tattoos tell”: to show the world the value of women in Amazigh society, at the cultural, artistic, economic, educational levels. Farmers, artisans, mothers, keepers of knowledge… Amazigh women were the pillars of their society. We wanted to tell their story through illustrations, texts, and tattoos, these poetic and mysterious messengers of their thoughts.

We hope that these few lines of thought will have enabled you to appreciate how rich and diversified the contribution of women to cultural transmission is!

But the subject of cultural transmission is endless, so see you very soon for other articles.